Spotlight on our Students: Jack Featherstone

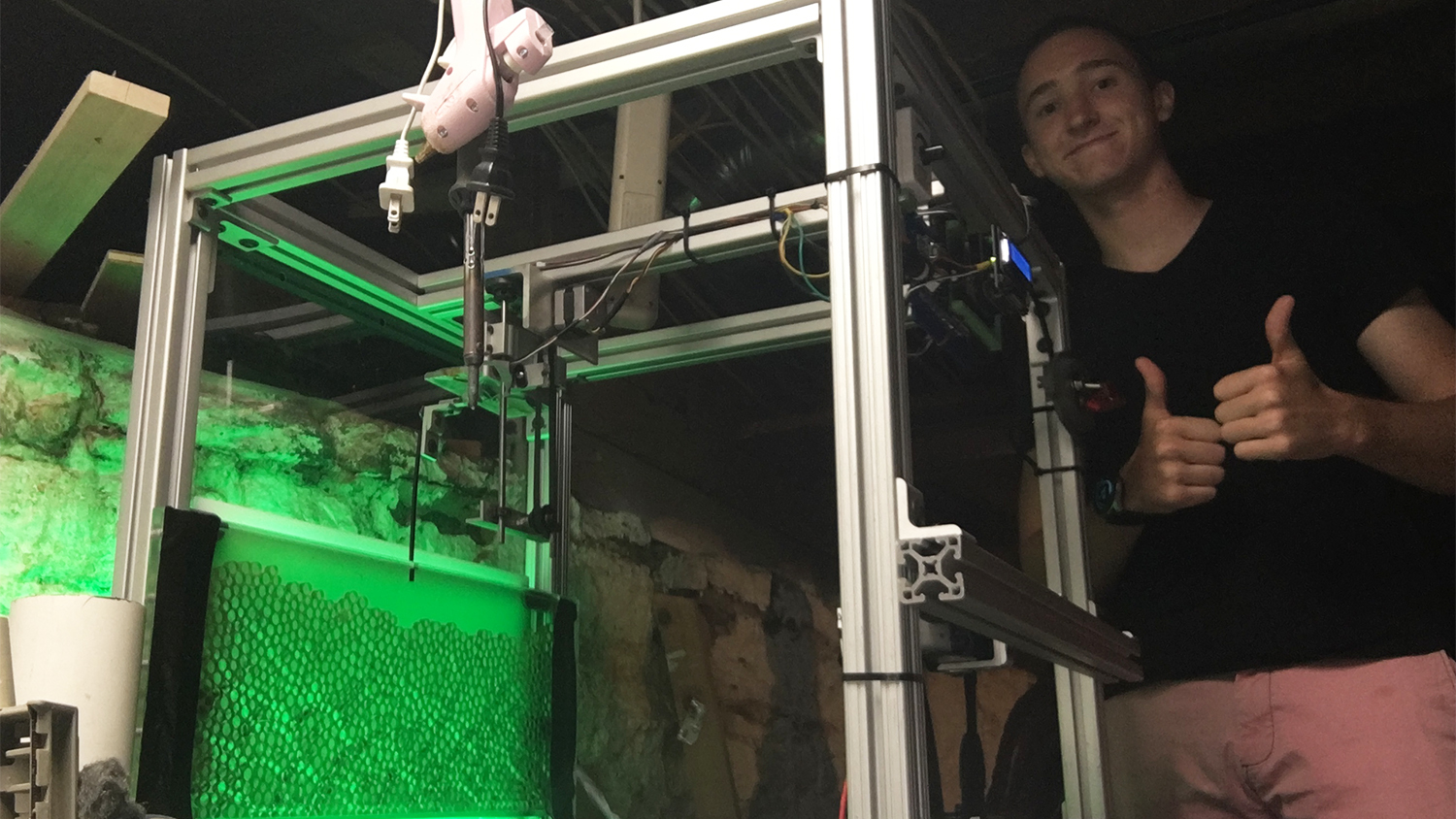

The University Honors and Scholars Programs interviewed Jack Featherstone, a third-year Honors Program student, about his research in granular physics principles in exotic environments — most of which he has conducted at home in his basement.

By Chester Brewer, assistant director of the University Honors and Scholars Programs

In this edition of Spotlight on our Students we are meeting with third-year University Honors student Jack Featherstone, who is majoring in physics, to learn more about his research investigating granular physics principles in exotic environments.

UHSP: Jack, thank you for taking time to tell us about the very interesting research you are working on. It sounds so foreign. To get us started, can you give us the main gist of what you are studying?

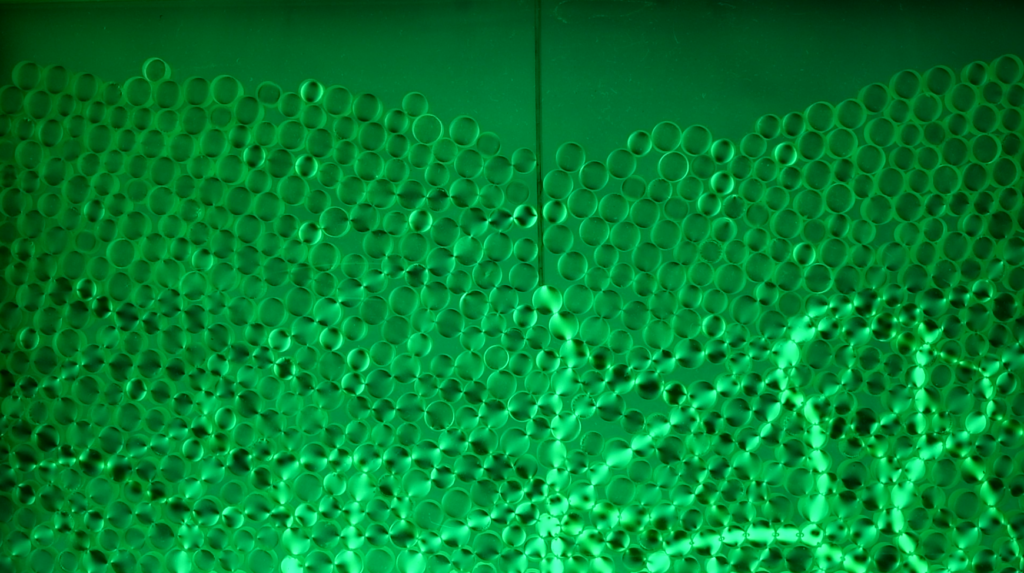

JF: Sure thing. I primarily work with Professor Karen Daniels investigating granular physics principles in exotic environments like asteroids or other planets. Understanding how to describe the physics in these places is really important when developing spacecraft instruments for sampling or anchoring (like on NASA’s OSIRIS-REx or JAXA’s Hayabusa2 missions). Granular physics is well suited to this pursuit because it is the study of how materials like sand behave, and the surfaces of most asteroids/planets are very grainy. We do this using experimental techniques that allow us to simulate the surfaces of these stellar objects while also measuring things like forces between grains. I work concurrently on another project that looks at how to predict when a granular material will fail (eg. during a landslide).

UHSP: That is super cool and very specific! What got you interested in this research?

JF: One of the main parts of the experiment for this project involves simulating grains in different levels of gravity, which was achieved by bringing the experimental apparatus on a parabolic flight. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to go on this adventure (very sad, I know), but I happened to have Dr. Daniels as a professor in my first year, during which she showed our class this experiment. I thought it was really cool, and so when I eventually ended up talking with her about possible projects, I chose to work on this one. The second project I mentioned (about predicting failure) is one that I designed myself with funding from a PPEP grant, mostly because I was interested in using machine learning on real data. Machine learning is what I am interested in studying for grad school, and so this was a really good way to tie together my current experience with what I want to eventually study.

UHSP: Very nice. So you found a way to plug in a genuine research interest of your own as well. What are you all hoping to learn from these studies? Are there potential applications for these models you are creating?

JF: For the first project, our goal is to present some preliminary results about what design aspects should be considered when creating spacecraft instruments that interact with asteroids/planets. While the procedures used in the OSIRIS-REx and Hayabusa2 missions were able to collect samples from two asteroids, there were some unexpected complications (eg. the former collected too much regolith, and some mechanical components were temporarily clogged by grains). Having a diverse set of tools will hopefully make future missions more robust, and less susceptible to issues — which is especially important since it takes ~2-3 years just to travel to these asteroids!

The second project has applications in geophysics, specifically to identify what is important in predicting whether a failure will happen in a collection of grains. We ask things like: will we get better results trying to predict a landslide using a topological map, or using measurements of the soil throughout a region?

UHSP: Both of those applications sound very useful and very timely. It’s super cool to see that the research you are conducting has a tangible impact. What has been the most interesting aspect of this work for you?

JF: I have really enjoyed working on the experimental aspect of the project, though it was a little unconventional (and therefore interesting) because I did most of the work in my basement. When we left campus last spring because of COVID-19, I drove the apparatus back to my home in Connecticut, and fixed it up and took data there!

UHSP: What!? Now that is dedication to a project. That’s great. What has been the most challenging part of this work? Aside from hauling the lab equipment back to your house in New England?

JF: Certainly the most challenging aspect of the project has been writing the publication, since it takes such a crazy amount of writing, rewriting, making figures, remaking figures, etc. I spent most of the Fall working on this, and we’re nearly done now!

UHSP: Congratulations! It is always a good feeling to be able to see the light at the end of the tunnel. What is something you have learned from this process?

JF: The experience of working in a real lab has been really helpful in developing a lot of the soft-skills that aren’t really taught in classes. This includes things like keeping good records and documentation of my work, effectively reading papers and collaborating with others. On top of this, it is pretty different from doing problems in classes, which always can be solved somewhat easily. Instead, in research you often have to come up with your own solution that you really can’t definitively prove right or wrong. I feel like a good amount of the time that I am doing my research is just getting used to this, and not expecting perfect results even after 10-plus attempts.

UHSP: YES! Learning the patience and resilience to overcome “failure” again and again is invaluable. How would you say your time in the University Honors Program has prepared you for this kind of in-depth research?

JF: The focus of honors seminars on writing was something that I initially dreaded, but it most likely has helped me immensely in my research, since doing research — regardless of the field — requires a lot of writing. Similarly, I have had the opportunity to present my research several times (and am currently preparing for a larger presentation right now), during which it was really important to recognize the interdisciplinary nature of my work. While I may have spent 80 percent of my time working on some niche analysis method, other people don’t really care about that stuff, so I had to frame my results in terms of what others find important. In my experience, this interdisciplinarity is a big focus of the UHSP, and so I am glad I was able to get a head start in this type of thinking.

UHSP: You are absolutely right about being able to translate your research findings into results that folks from other disciplines can understand. Otherwise, you’re siloed into only talking about the work with your immediate colleagues. Lots of UHSP students participate in research during their time at NC State. What advice would you give upcoming students on how to get engaged in research?

JF: That it’s totally normal to feel like you understand nothing about a research project or field as you are starting off. Even now I still will read a paper and have to look up words like every other sentence, but that doesn’t mean I’m incapable of contributing to the project. In my experience, this felt incredibly overwhelming at the beginning, but that’s quite normal, and try not to get discouraged by it.

UHSP: Oh yes, it can seem like you are constantly learning a foreign language; and in a sense you are, right? Best to take it bit by bit and celebrate the small advances you make in your own understanding of the material. In closing, can you tell us the best bit of advice you’ve ever received?

JF: Definitely the most helpful thing I’ve been told about doing my research is that the amount of effort you put in doesn’t always exactly relate to how much progress you make on a project, but it doesn’t mean that time was wasted. Towards the beginning, I tended to worry that if I spent 10 hours one week on trying to understand a concept instead of writing more analysis code, I was not working efficiently. My PI assured me (and continues to do so, since it’s natural to want physical deliverables) that time spent developing your understanding of a topic, or reviewing concepts, or anything else that isn’t direct progress, is just as valuable as anything else.

UHSP: It is great to think of learning as a cycle and not always a linear path that we are led to believe it might be, right? Well, Jack, thank you again for taking the time to talk with us about this work. And best of luck on your upcoming presentation of this material.