Endless Possibilities: The Fearless Creativity of Mary Ann Scherr

By Kelly McCall Branson

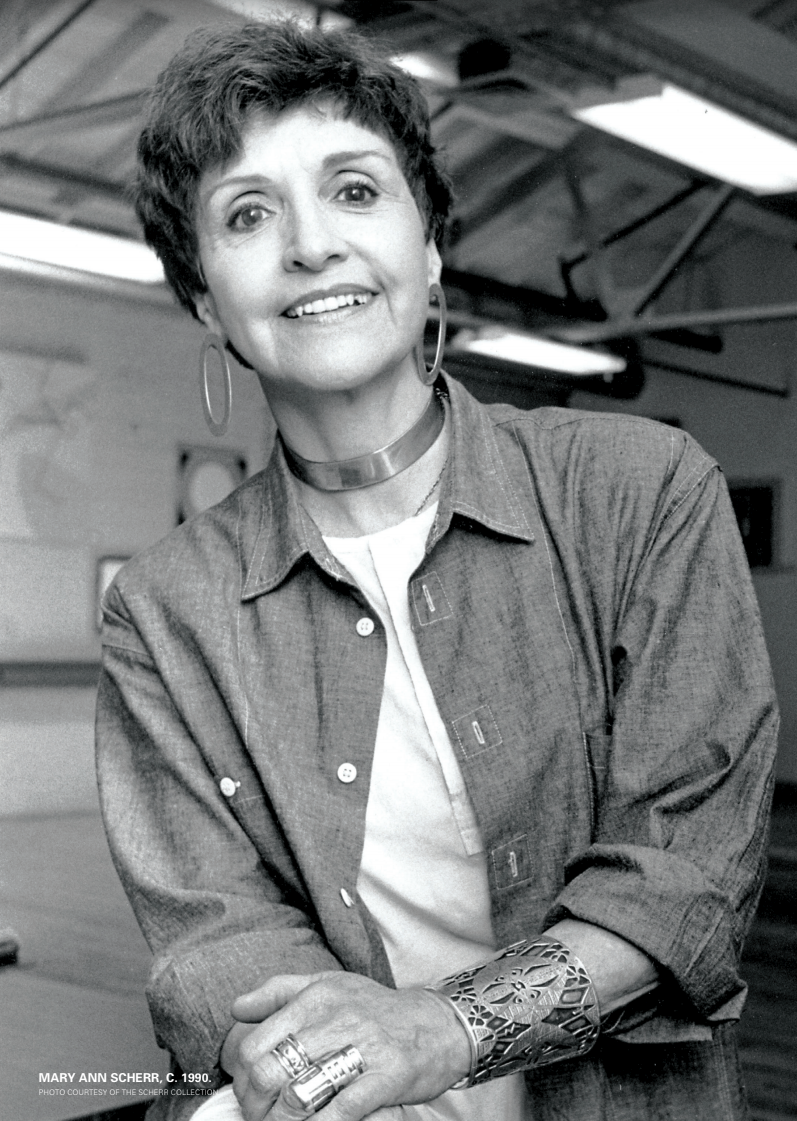

When internationally renowned jewelry maker Mary Ann Scherr first fell in love with metal, back in the 1940s, it wasn’t the slightest obstacle to her newfound passion that there existed only one, rather incomplete textbook on the subject of jewelry making; she simply launched her own mission of discovery – seeking out the expertise of chemists, engineers, and metal workers, and spending countless hours in experimentation in her home studio – all with the kind of ravenous curiosity and unwavering persistence that was the hallmark of virtually every day of Mary Ann Scherr’s 94 years.

Scherr told writer Blue Greenberg in a 1990 interview: “For me, art is not just the action of the maker; it is the investigation, the learning, the change, the discovery.”

The retrospective of the work of this industrial designer, illustrator, writer, graphic artist, educator, inventor, and goldsmith – on exhibition February 21 through September 1 at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design – is a tangible testament to the utterly unstoppable, seemingly limitless and marvelously fearless creativity that was Mary Ann Scherr.

Her prominent clients included the Duke of Windsor, Chelsea Clinton, and Ralph Lauren. Her work is held in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Renwick Gallery, the Vatican Museum of Contemporary Art and the Goldsmith’s Hall in London. She received copyrights and patents for her innovations in metal etching and wearable medical devices. She won countless awards and accolades and is considered one of the most influential metalsmiths of the 20th century.

Some of Scherr’s bracelets and rings bear the phrase “All is Possible,” and for the curator of this retrospective, Ana Estrades, this summed up the essence of the woman and her work; hence the exhibition’s title, All is Possible: Mary Ann Scherr’s Legacy in Metal. “‘All is Possible’ communicates Mary Ann’s zest for life and also the many creative possibilities she saw in metal design,” says Estrades, a jewelry historian, designer and teacher. “The title refers to so many layers – the challenges of a woman working in her time, the diversity of her work, when she chose metals, all that her energy, her ability, her creativity made possible.”

AN ILLUSTRIOUS HISTORY

For the last 25 years of her life, Mary Ann Scherr called Raleigh home, and her influence on the local arts scene over that time was far-reaching and her accomplishments impressive, but this was only a fraction Scherr’s creative resume.

With a career spanning some seven decades, she spent her entire adult life exploring, creating, innovating – and reinventing herself. She often commented that her life read like a telephone book and that once anything became too familiar, she had to move on. Scherr worked as a graphic designer, a dancer, an illustrator, a cartographer, an industrial designer, a fashion designer, a teacher, an inventor and, of course, a metalsmith. And she excelled at every endeavor.

She was the first woman hired to the automotive division of Ford Motor Company, where she designed hood ornaments and car interiors. She and her husband Sam co-founded Scherr & McDermott, one of the leading industrial design firms in the world at the time. There, she designed everything from rubber toys to umbrellas to boots.

A cookie jar she created was snapped up by Andy Warhol for his collection and later sold at auction for $19,000. Always a fashionista – when Scherr experienced firsthand the less-than-elegant maternity wear of the day, she created her own line of chic maternity dresses (sketches of which are in the Gregg collection).

It was just after the birth of her first child that, as Scherr liked to put it, she “backed into metals” and discovered one of her true lifetime loves. Her experience as a stay-at-home housewife and mother left her feeling stifled. So Scherr enrolled in a beginning jewelry-making class, chosen mainly because it fit her schedule. And she was hooked.

The infinite possibilities presented by a blank sheet of metal – of cutting and shaping, coloring and marking, piercing and layering, of the chemistry and physics and engineering and even biology involved – this, for Scherr, was irresistibly alluring. More than 50 years later, shortly before her death, she commented in an interview that she was still investigating new techniques with metals and might never learn all there was to know.

With a single textbook to guide her in the beginning, she dove in headfirst educating herself, experimenting. A pair of earrings she designed in 1951 won a prize. Within two years, Scherr was teaching all the metals courses at the Akron Art Institute.

Scherr’s insatiable curiosity led her to pioneer techniques in exotic metals. Her jewelry is crafted from pyrite, sliced walrus tusk, jade, granite, glass, titanium, quartz, stainless steel, aluminum and more. She seemed to find the soul in every material she worked with, most particularly metal, saying in a 2001 interview with the Smithsonian Institution, “there’s something gentle about pewter; there’s instant magic with titanium; something precious about gold; silver is endless; iron is a proud, handsome metal; and aluminum is quixotic.”

In addition to her prolific design work, Scherr was devoted to sharing her skills and wisdom. “She was absolutely driven to share her knowledge,” says former NC State Crafts Center director George Thomas. “And had devised such great methods for simplifying and demonstrating.” Scherr was an educator her entire adult life, chairing the graduate program in metals at Kent State University for 27 years and later overseeing the product design department at the Parsons School of Design in New York for a decade. Scherr began teaching at the Penland School of Crafts in 1968 and was their longest-tenured instructor.

In 1969 Scherr was commissioned to create a space-themed costume for Miss Ohio. As she worked late one night on the stainless-steel belt of the ensemble, she watched the grainy images of the astronauts walking on the moon. A lightbulb went off. Why couldn’t the decorative belt she was fashioning to look like it carried a readout of the wearer’s heartbeat actually work?

And so, a new lifelong passion was born for Scherr. She saw – decades before the advent of the Fitbit – the possibilities for all manner of compact, wearable, elegant body monitors for heart rate, air quality, respiration and temperature.

The very next week, she visited the biology department, the chemistry department and the Liquid Crystal Institute at Kent State University. When one academic scoffed that her air quality sensor would require an 11- by 15-foot wall, she found another electronic engineer who, within a month, reduced that size to a 4.5 square inch electronic field. That pendant is now in the American Craft Museum’s permanent collection.

Scherr spent the rest of her life exploring and experimenting with body monitors. The belt she designed for Miss Ohio was donated to the Gregg Museum by a Raleigh collector.

THE RALEIGH YEARS

In 1989, when Mary Ann and Sam Scherr decided to move from New York City to Raleigh to be closer to their three children, the local arts community wasted no time in embracing her. “I got a phone call that a famous jewelry designer was moving here,” says longtime friend, student and collaborator Patsy Hopfenberg, “so I called Mary Ann in New York. I wanted to get to her before people knew she was coming, and I asked her to serve with me on the Friends of the Gallery [now the Gregg Museum] Board.” Without hesitation, Scherr agreed.

As with everything she did, Scherr threw herself into this new phase of her life with relish. She joined the Raleigh Fine Arts Society and co-founded the artist cooperative gallery, The Roundabout. “She was just such an inspiration to all of the artists at Roundabout,” says fellow founder Susan Woodson. “She encouraged everyone. She worked harder than everyone. I have her ‘Hell Yes!’ bracelet. That really was Mary Ann’s can-do attitude all the time.” In addition to her flourishing jewelry business, and her extensive community service with arts and animal organizations, Scherr taught classes at Duke University, Meredith College, at NC State in the College of Design and at the Crafts Center, as well as in her home studio. “Taking a class with her was one of the best experiences of my life,” says author and NC State professor, Marsha Gordon. “She had this gift of encouraging her students to dream big.” Local artist Joyce Watkins King concurs. “She just had a way of giving you permission to pursue what you wanted to pursue. She didn’t push her own ideas but helped her students to bring to life their own ideas.”

Her students report her uncanny ability to break down complex processes into digestible bites. “She had this system of simple steps that was so easy to follow,” says Woodson, “but you never felt like you were just following the rules – it was so creative.”

Hopfenberg almost didn’t register for the class she took with Scherr at Duke; it was inconvenient, not a good time. But somehow, she knew she should make the time, and that class would begin a 27-year friendship and collaboration that would change the course of her life. “She was a force of nature,” says Hopfenberg. “When Mary Ann walked into a room, it was like a bright light had been turned on. She had such energy.”

One of the great delights of her friendship with Mary Ann was the opportunity to borrow spectacular pieces from Scherr’s collection. “She would say, ‘just get a black dress, and I’ll take care of the rest,’” says Hopfenberg. “She lent me a necklace with 40 Harry Winston diamonds to wear to the Playmakers ball one year. You can’t imagine the attention I got.”

Scherr also worked closely with apprentices and assistants in her studio, many of whom have gone on to flourishing jewelry careers of their own. She believed that true talent should be encouraged and nurtured and never hoarded her little tricks and secrets for herself, but shared with abandon all she could.

Local jewelry designer Suijin Li Snyder began working with Scherr after taking one of her classes in 1992. “It was just a little taste, but I knew – this is not enough!” says Snyder, who went on to complete a two-year apprenticeship with Scherr. “She was always so encouraging,” says Snyder. “Even when there were mistakes, she only saw the possibilities there – to fix it or to learn from it or to make something new.” Snyder remembers fondly their trips to the hardware store, where Scherr would inevitably discover some treasure she was sure to have a future use for. “She saw possibilities in everything,” says Snyder.

Sarah Tector, of Raleigh’s S. Tector Metals, worked as Scherr’s studio assistant right out of college. She was struck by both the generosity of Scherr, with her wisdom and her skills, but also by the trust that Scherr showed in Tector’s talent. “That level of respect was so affirming,” says Tector. “It was her name that went on this work, but she had enough faith in my abilities to let me do the work.” Tector executed Scherr’s design work on the NC State chancellor’s medallion and years later, when modifications were made to the piece, Tector was selected to do the fabrication. (This medallion will be displayed in the Gregg exhibition.)

Another local jewelry designer, Megan Clark, spent three years in Scherr’s studio. “She was fierce!” says Clark. “She was tiny, but her physical strength and her energy – in her eighties! She gave me such a different perspective on what it means to grow older.”

RETROSPECTIVE

Scherr’s influence in the Triangle was considerable, through her classes for both hobbyists and serious artists, her activism for the arts and animal organizations and, of course, her prolific work. “I was at an arts event once,” says Marsha Gordon, “and I looked around the room and said, ‘I think everyone in this room has taken a class from Mary Ann Scherr.’”

When curator Ana Estrades began her search for work to include in Scherr’s All is Possible exhibition, she turned first to the local community. The response was astonishing. So much so that pieces from 15 local lenders, including Scherr’s two sons, will be included, making up the bulk of the retrospective. Pieces on loan from Scherr’s daughter Sydney and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York will also be exhibited.

Patsy Hopfenberg’s most cherished piece is an elaborate niello neckpiece with the cross-section of a Samurai sword. It was left to her by Scherr in her will. Joyce Watkins King treasures a necklace that she purchased from Scherr’s estate, a heavy gold “Nubian” necklace, etched with a series of circles – one that Scherr wore often.

Her “message” pieces are particularly valued by area collectors. In addition to the “All is Possible” mantra, and Woodson’s “Hell Yes!” cuff, Scherr created (and wore) a sassy“Bite Me” belt. She appliqued thousands of zodiac symbols, animal spirit icons and significant numbers and phrases onto necklaces, bracelets, rings and key fobs.

The work exhibited at the Gregg will span more than six decades of Scherr’s creative achievements. Some of her former assistants will model her jewelry at the opening, and visitors are encouraged to wear their own Mary Ann Scherr pieces. “I want museum visitors to explore this jewelry in its full complexity as much more than just a fashion accessory,” says Estrades, “but as works of art, meaningful design, personal expression.”

Indeed, the works of Mary Ann Scherr are a window into the indomitable spirit and the astounding creativity of the woman so beloved in the Triangle and beyond.

Kelly McCall Branson is a freelance writer who has written about the arts, dining, travel, sustainable living and home building for regional and local publications throughout the Southeast.

This article was originally published in the spring 2020 issue of #creativestate, the official magazine of Arts NC State.

- Categories: